Author: Magda Popiashvili

On 2 October 2021 we will be voting once again to elect city mayors and members of assemblies [sakrebulo]. Since the restoration of independence, this will be the eighth time that we, Georgia’s citizens, will have to elect local authorities in our municipalities.

Much has changed since 1991 – governments changed as did the models of authority delegation, self-governance systems, and rules for local elections; unfortunately, however, 30 years from the first elections, we still have not achieved fully developed system of local governance. Let us take a long look at those we placed our trust in from one self-government election to another over these thirty years. This review intends to give a clear depiction of the gradual decline of local self-governments as decentralization was rejected and the centralized rule gained ground.

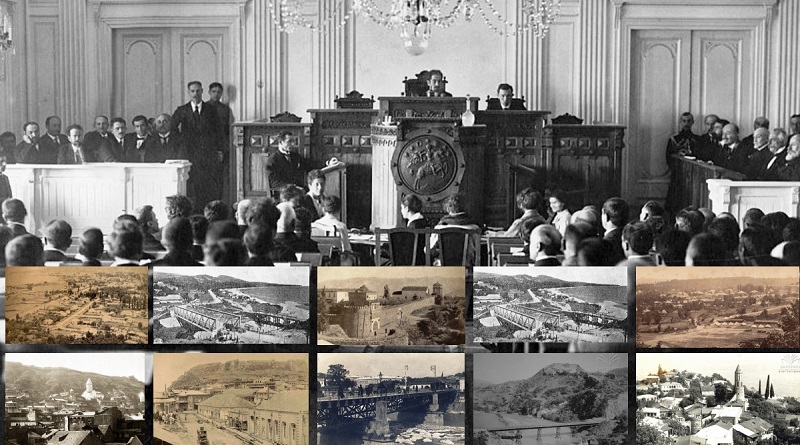

31 March 1991 – two levels of self-government, elected assemblies, and appointed prefects

The date, in the first place, is imprinted as especially significant and noteworthy in the national memory due to another event – a referendum for independence, which restored the country’s sovereignty. Thus, perhaps, many people might not remember that Georgia also held its very first local elections 30 years ago.

What kind of a self-governance system did we have back then, and what was the rule for the election of local authorities?

Georgia met its first local elections with a two-level system of local self-governance. This was, certainly, far from an ideal, fully functioning, well-developed system of self-governance, and it was in serious want of many administrative / territorial reforms and competency differentiation; however, at that time, in the wake of the country’s newly regained independence, even such a flawed model seemed to provide a solid ground for the implementation of effective self-government reforms in the future. Major principle underlying the concept of self-governance is that local authorities were as close to their people as they can be.

The first level of self-government included communities, urban-type settlements, villages, towns, and city districts (for example, in case of Tbilisi, assemblies were elected for the capital’s individual districts), while regions and multi-district cities of republican subordination formed the second level (e. g., current self-governing cities, etc.).

An assembly [Sakrebulo] has been a representative body for already thirty years at both levels of self-government, however, in those days, we could only elect members of first-level assemblies, while the representative bodies of regions or multi-district cities would not be directly elected; instead, they were composed of deputies, i.e. chairs and representatives of the first-level assemblies. The same was true of the capital’s assembly, which united 70 reps of Tbilisi’s 10 regions (7 from each) and three members from the Tskneti settlement.

Executive bodies of the upper and lower levels differed in a number of ways: the lower level of villages, settlements, communities, towns, and city districts were governed by a Gamgebeli [governor], while the upper level – regions and cities of republican subordination – had prefectures, and Tbilisi was governed by a mayor. Back then, we elected neither Gamgebelis, nor prefects or city mayors. The latter two would be usually appointed first by the Supreme Council and then by the president. As for Gamgeleblis, who were in charge of the first-level governing units [Gamgeoba – governor’s office], the prefect was elected from assembly members.

Notwithstanding the two-level self-government model and direct election for the first level representative bodies, appointment of prefects and the capital’s mayor helped the central government to maintain its tight grip of the local authorities.

The elections were held through the system of single transferable vote (STV). This was a major reason behind the fact that the assemblies united diverse parties – the minor ones and the larger, dominant alliance of Round Table – Free Georgia. Most importantly though, many independent candidates were also elected to the office. For example, independent candidates nominated by initiative groups constituted 22% of the elected members to the capital’s assemblies.

Following the 1991 self-government elections, the assembly members included representatives of the Round Table – Free Georgia alliance, the National Front, the Democratic National Front, the Independent Communist Party, the National Party of the Demographic Society, the Alliance of Liberation and Economic Revival, the Lema Society, Georgian political and civic organization Svaneti, the Union of Young Christian-Democrats, the Union of Georgian Farmers, the Party of Georgia’s National Integrity and Social Equity, and other political groups. As we have already mentioned, along with party members, independent candidates nominated by initiative groups also demonstrated good results and were elected to the assembly.

Following the 1991 self-government elections, the assembly members included representatives of the Round Table – Free Georgia alliance, the National Front, the Democratic National Front, the Independent Communist Party, the National Party of the Demographic Society, the Alliance of Liberation and Economic Revival, the Lema Society, Georgian political and civic organization Svaneti, the Union of Young Christian-Democrats, the Union of Georgian Farmers, the Party of Georgia’s National Integrity and Social Equity, and other political groups. As we have already mentioned, along with party members, independent candidates nominated by initiative groups also demonstrated good results and were elected to the assembly.

However, following the civil war of 1991-1992 and the violent coup of government, local self-governments stopped functioning. Based on the Decree of 4 January 1992, the Military Council abolished the elective bodies, and the authority was granted to extraordinary commissioners. Not long afterwards, the central authorities established the direct rule.

15 November 1998 – results that prevented the governing party from obtaining the majority in Georgia’s most large towns and cities

For 8 years since 1991, the country was burdened with too many major problems to focus on self-government elections, and it was not until 1998 that the elections could be finally held.

Looking back, we may boldly declare that these elections ensured the most pluralist assemblies, which fundamentally differentiates it from its successors in the following years.

Most importantly, perhaps, it was at this election that the then governing party – the Citizen’s Union of Georgia (CUG) failed to form the majority in the large cities and towns of the country. Thanks to this, a sizable proportion of the assemblies was occupied by the opposition’s majority. For example, it was exactly during this period that Lado Kakhadze, candidate of the opposition’s Labour Party, became the chair of the capital’s assembly.

The development of the first and more or less complete legal basis added to the importance of these elections, and the Parliament passed the law On Local Self-government and Governance. However, as its very title suggests, the law regulated both self-governments and local governance, which means that we basically maintained the system of quasi-self-government in 1998. Sadly though, it was exactly in this period that the government could have supported decentralisation and turned it into an irreversible process to achieve genuinely powerful, independent, and self-sustained local authorities. Unfortunately, the governing elite under President Shevardnadze refused to further support the development of self-governments.

Throughout the period, Georgia had still maintained the two-level model of self-government, with minor differences from the original one of 1991: the first level included villages, communities, urban-type settlements, and towns, where the population directly elected members of the representative bodies. Gamgebelis automatically became assembly chairs. At the second level (regions and cities of republic subordination), assemblies were elective, the Gamgebelis, however, were appointed by the president.

Another noteworthy aspect [about the 1998 elections] was the fact that majoritarian system was used for 653 assemblies with fewer than 2000 eligible voters, while members of 378 assemblies with more than 2000 voters were elected through the proportional representation system. Further, a party was allowed to participate in the proportional representation elections only if it had submitted its electoral lists in at least 50% of the overall number of the proportional representation districts. Such a precondition artificially reduced the number of political units willing to participate in the local elections. Overall, 10693 members had to be elected to 1031 assemblies during the 1998 elections.

Unlike the 1991 self-government elections, the one in 1998 saw active political campaigns held by many political parties and candidates. This included meetings with population, dissemination of posters and leaflets, and crowded concerts arranged by the governing party.

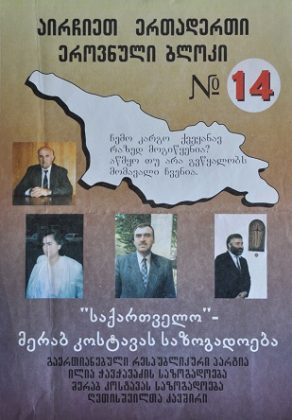

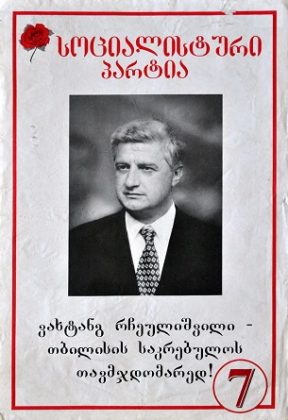

“Strong Party in the Assembly” (Citizens’ Union), “[We Shall] Save Tbilisi Together”, “Let’s Get Down to Business” (Green Party), “Choose the Only National Alliance” (Georgia – Merab Kostava Society) – these are the mottos that several parties used as part of their campaigns.

Tbilisi mayorship candidate Lado Kakhadze from the Labour Party promised his electors that he would serve as pregnant Tbilisi’s midwife, strange as it may sound. Though we never saw him act that role, he still achieved the status of the Assembly chair. Soon afterwards, he abandoned the party and allied with Shevardnadze’s party. Later, Shalva Natelashvili – the leader of his former party, referred to Kakhadze as the ‘full-time Tamada’ for the Citizens’ Union.

Tbilisi mayorship candidate Lado Kakhadze from the Labour Party promised his electors that he would serve as pregnant Tbilisi’s midwife, strange as it may sound. Though we never saw him act that role, he still achieved the status of the Assembly chair. Soon afterwards, he abandoned the party and allied with Shevardnadze’s party. Later, Shalva Natelashvili – the leader of his former party, referred to Kakhadze as the ‘full-time Tamada’ for the Citizens’ Union.

Overall, seven political parties crossed the threshold and entered the capital’s Assembly; governing party – the Citizens’ Union accumulated only 29.94% of votes, the Labour Party – 17.90%, Socialist Party – 12.66%, National Party – 7.40%, Democratic Union of Revival – 7.02%, National-democratic party – 6.65 %, and Union of Traditionalists – 6.09%.

Except for the capital, the Citizens’ Union of Georgia (CUG), was defeated and the opposition obtained majority in Batumi, Poti, Kutaisi, and Rustavi; further, the governing party failed to obtain the majority in 33 of 65 regions.

Despite the success the opposition achieved in regions, elections held in Adjara Autonomous Republic (Adjara AR) under Aslan Abashidze’s governance saw no representatives of either CUG or the opposition elected to the AR’s assemblies as all posts were occupied by the members of the Revival Union of Georgia.

2 June 2002 – first direct election of mayors and Gamgebelis, failure of the governing party, and a dress rehearsal of the parliamentary elections

Despite the loss it suffered in 1998 elections, the government made an unusually bold step by deciding on the direct elections for mayors in cities of republican subordination and regional Gamgebelis. Overall, 40 mayors and Gamgebelis were directly elected in 2002. Two cities remained an exception – Tbilisi and Poti, where mayors would still be appointed by the President.

When it comes to the elections of assemblies, voting rules for the first-level self-governing bodies remained unchanged, and the chairs of assemblies still maintained governor’s authority in villages and communities.

Notwithstanding the legislative amendments of 2001, the government did not take the risk of establishing local self-governance at the second (regional) level and maintained the model of local governance. This might have served the purpose of controlling the elected officials in the first-level self-governing bodies. However, the introduction of mayoral and governor’s elections at the first level is indeed a noteworthy decision, a major step taken in pursuit of democracy, especially, against the background of 1998 election results and the challenging political situation that persisted in the country throughout the period.

A regional-level assembly consisted of the chairs of first-level self-governments – assemblies of villages, communities, and towns encompassed within the region. The regional assembly had a speaker elected by the assembly from among its members. The region’s governor would be also selected from among the assembly members and appointed to the office by the President of Georgia.

In a word, similar to 1998, 2002 also saw a hubbub of local self-governance and governance, which, of course, prevented self-government from developing into an independent institution, especially, considering the fact that the central and local authorities lacked clearly defined competencies, duties and responsibilities, and the self-government’s executive and representative bodies had many overlapping powers and functions; and despite the high level of financial decentralisation (income, property, and profits tax remained in local budgets), poor quality of administration and burgeoning corruption in the country curtailed the public finances. Taken together, these factors did not allow for the establishment of a fully independent self-government.

Although Sehvardnadze had declared 2 June as the date for the elections, Aslan Abashidze – the leader of Adjara AR did not obey the order and held the local self-government elections in his region two weeks later – on 16 June. No elections were conducted in the territory of former autonomous regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

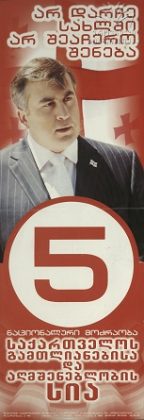

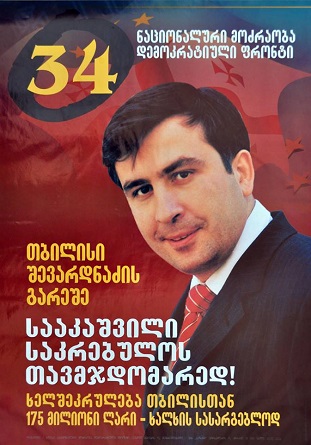

You might well remember the political situation in Georgia before the local elections – the opposition viewed these elections as the dress rehearsal of 2003 parliamentary elections. The United National Movement (UNM) – then an emerging opposition party born out of the CUG and composed of the latter’s former members – aimed to defeat the governing party (CUG) and then ensure the change of government at the parliamentary elections. “Tbilisi without Sehvardnadze!”, “Saakashvili as the Head of the Assembly!” “A Deal with Tbilisi – 175 million GEL to the Benefit of its People” – these were the UNM’s major mottos, then a prominent opposition party.

You might well remember the political situation in Georgia before the local elections – the opposition viewed these elections as the dress rehearsal of 2003 parliamentary elections. The United National Movement (UNM) – then an emerging opposition party born out of the CUG and composed of the latter’s former members – aimed to defeat the governing party (CUG) and then ensure the change of government at the parliamentary elections. “Tbilisi without Sehvardnadze!”, “Saakashvili as the Head of the Assembly!” “A Deal with Tbilisi – 175 million GEL to the Benefit of its People” – these were the UNM’s major mottos, then a prominent opposition party.

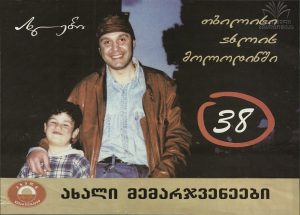

New Rights party was another formidable power, whose leaders entered the parliament in 1999 as the CUG’s members. Levan Gachechiladze, the leader of the Rights, gave up his mandate ahead of 2002 self-government elections, hoping that the new party would obtain a convincing victory, which would make him the Assembly’s chair. The party’s motto voiced their intentions – “Tbilisi is Waiting for the New”. Campaign posters featured Levan Gachechiladze’s brother, singer Utsnobi [Stranger], who was actively engaged in the campaign and prepared the party’s branding video “[I am] Waiting for the Sun” specifically for the elections.

New Rights party was another formidable power, whose leaders entered the parliament in 1999 as the CUG’s members. Levan Gachechiladze, the leader of the Rights, gave up his mandate ahead of 2002 self-government elections, hoping that the new party would obtain a convincing victory, which would make him the Assembly’s chair. The party’s motto voiced their intentions – “Tbilisi is Waiting for the New”. Campaign posters featured Levan Gachechiladze’s brother, singer Utsnobi [Stranger], who was actively engaged in the campaign and prepared the party’s branding video “[I am] Waiting for the Sun” specifically for the elections.

Besides, the Labour Party was still enjoying great success and popularity. In a word, the governing party met the 2002 elections with severely weakened positions – on the one hand, they were facing a range of very strong opponents, and, on the other – high level of public discontent and street rallies in the capital.

Not long before the election date, the Citizens’ Union almost dropped out of the race due to the fact that the party’s general secretary and its distinguished leader Zurab Zhvania left the Union along with some of his followers. As Zhvania’s signature stood on the party list filed for the participation, the Central Elections Commission decided to cancel the CUG’s submission on 13 May 2002. However, five days before the elections, on 27 May 2002, the Supreme Court ruled that the Citizens’ Union would remain in the voting papers.

Before leaving the party, Zurab Zhvania declared that Citizens’ Union would be an opposition party. He demanded that he and his team were allowed to represent this party in the elections, however, Tbilisi City Court ruled against Zhvania’s team and forbade them to represent the CUG in the local elections. Zhvania left the Citizens’ Union 4 days earlier and represented hitherto unknown and newly established Christian-Conservative Party in the self-government elections.

Before leaving the party, Zurab Zhvania declared that Citizens’ Union would be an opposition party. He demanded that he and his team were allowed to represent this party in the elections, however, Tbilisi City Court ruled against Zhvania’s team and forbade them to represent the CUG in the local elections. Zhvania left the Citizens’ Union 4 days earlier and represented hitherto unknown and newly established Christian-Conservative Party in the self-government elections.

This grave and tense political background, of course, reflected itself on the election day, leading to the suspension of elections in Zugdidi, Rustavi, and Khashuri. These electoral districts had to revote on 16 June; in Kutaisi, where Nugzar Paliani of the Rights won the mayoral elections, several lawsuits contested the election results.

Results of 2002 self-government elections proved especially interesting and dramatic: the CUG lost its governing status, which it never regained. It failed to cross the threshold in Tbilisi, accumulating only 2.37% of votes. The party only managed to finish in the 9th place all over Georgia with a total of 70 mandates.

Georgia’s Labour Party secured the first place and the respective 15 mandates in the city’s assembly with 24.99% of votes, while the second place went to the alliance of the United National Movement – Democratic Front – Saakashvili, Davitashvili, Shavishvili, Dzidziguri, Berdzenishvili. Despite the first place obtained by the Labour Party, you might remember that the UNM’s leader Mikhail Saakashvili became the assembly chair.

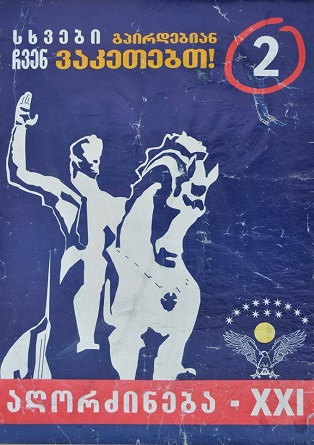

A total of 7 political units crossed the electoral threshold in Tbilisi. In addition to the Georgian Labour Party and the National Movement, the representatives of the following parties entered the Sakrebulo (City Assembly): the New Rights Party (Akhlebi [the New Ones]) – 11.10% and 7 mandates; the Christian Conservative Party of Georgia – Zurab Zhvania’s Team“ – 7.20% and 4 mandates; electoral alliance Industry Will Save Georgia – 6.81% and 4 mandates; electoral alliance Revival XXI – 5.63% and 3 mandates; Ertoba [Unity] – J. Patiashvili, Al. Chachia – political union Ertoba, Realists’ Union of Georgia – 4.03% and 2 mandates.

Outcomes of the elections in other regions all over the country proved even more interesting, closely reflecting voters’ attitudes towards the existing parties. 58% of 4801 mandates (which amounts to a total of 2 754 mandates) went to independent candidates nominated by various initiative groups, leaving only 42% for political units, among which the New Rights managed to gain the leading position. The latter obtained a total of 551 mandates. The Labour Party, having secured the highest number of votes in Tbilisi, received the overall number of 152 mandates, while the National Movement failed to obtain more than a single mandate outside Tbilisi.

Based on the CEC’s (Central Election Commission of Georgia) results, of 41 parties engaged in the elections all over Georgia, only 15 of them managed to overcome the electoral threshold: 1. the New Rights (Akhlebi) – 551 mandates, 2. electoral alliance Industry Will Save Georgia – 481 mandates, 3. Electoral alliance Revival XXI – 198 mandates, 4. the Socialist Party – 189 mandates, 5. Labour Party of Georgia – 152 mandates, 6. the Party for the Protection of Constitutional Rights – 116 mandate, 7. the National-Democratic Party – 86 mandates, 8. Lemi – 73 mandates, 9. Citizens’ Union of Georgia – 70 mandates, 10. the alliance of the National Movement – Democratic Front – 15 mandates, 11. the alliance of the National Party –

Based on the CEC’s (Central Election Commission of Georgia) results, of 41 parties engaged in the elections all over Georgia, only 15 of them managed to overcome the electoral threshold: 1. the New Rights (Akhlebi) – 551 mandates, 2. electoral alliance Industry Will Save Georgia – 481 mandates, 3. Electoral alliance Revival XXI – 198 mandates, 4. the Socialist Party – 189 mandates, 5. Labour Party of Georgia – 152 mandates, 6. the Party for the Protection of Constitutional Rights – 116 mandate, 7. the National-Democratic Party – 86 mandates, 8. Lemi – 73 mandates, 9. Citizens’ Union of Georgia – 70 mandates, 10. the alliance of the National Movement – Democratic Front – 15 mandates, 11. the alliance of the National Party –

Traditionalists’ Union – 15 mandate, 12. Merab Kostava Society – 9 mandates,

13. Tanadgoma – 7 mandates, 14. the Ertoba alliance – 4 mandates, 15. the United Communist Party and Labourer Councils – 1 mandate.

Results of self-government elections held in Adjara AR are especially notable. Traditionally, representatives of Abashidze’s alliance – Revival XXI – were elected to all self-governments of the region, while Aslan Abashidze’s son Giorgi Abashidze became Batumi’s mayor.

5 October 2006 – the first level of self-government is abolished; mayors and Gamgebelis are no longer elective, and the full authority rests with the governing party

2006 self-government elections were the first municipal elections held under the rule of the United National Movement (UNM) after the Rose Revolution. Since 2003, the governing party began the modernisation of the country. Years later, many leaders of the party have admitted that this modernisation, fight against corruption as well as other steps taken at that time prevented the governing elite from assisting the development of self-governance, which led to the full concentration of power within the hands of the central government.

This ‘modernisation’ in 2005 took its toll on the small and minor improvements made in the attempt of institutional empowerment 3 years before – upon the announcement of the results of 2006 self-government elections, Organic Law of Georgia on Local Self-Governments was enacted, abolishing self-governments at the first level – i.e. in villages, towns, urban settlements, and communities. This meant that the country moved to one-level, district-based (as districts were defined back then) system of self-government. It was at this time that the self-governing units changed their names, and a new term ‘municipality’ was introduced to refer to what was traditionally known as a “district”; towns of republican subordination gained the status of administrative centres within municipalities, while Tbilisi, Rustavi, Kutaisi, Poti, and Batumi became self-governing cities.

Overall, before the onset of 2006 elections, only 65 municipalities survived out of more than 1000 self-governing units that existed in 1998.

Another step backward that the so-called reform of 2005-2006 brought about was the abolition of mayoral and Gamgebeli elections. The UNM’s team decided that municipal Gamgebelis and mayors of self-governing cities should not have been directly elected to the office by the population, and the assemblies had to appoint them.

The governing elite tried to explain this decision by claiming that it would increase the effectiveness of local governance, release more financial resources that had been previously distributed between the first and the second levels and enhance the quality of public services. However, the result was a centralized system: in the wake of the abolition of the first-level self-government, the central government launched the process of financial centralisation instead of continuing and upholding decentralisation (for example, profits tax was fully directed to the central budget), and the municipalities became increasingly dependent on transfers from the central budget. The local self-governments were now in charge of the increased population, and if during the existence of the first-level government population of a single self-governing unit ranged between 4 to 5 thousand people, the numbers soared dramatically, hitting 60 to 100 thousand people [per a self-governing unit] after the abolition of village, town, and community self-governments. Such a decision not only indicated no improvement of municipal services, but, more importantly, contradicted the European Charter of Local Self-Government signed by Georgia in 2004 and the general principle behind self-governance – the closer the self-government is to its people, the more effective it is.

Winner takes it all – the road to Europe lies across Chad, Cameroon and Djibouti …

Before we discuss the election results, I would like to note here that the election system itself changed and differed from the one in force during the previous elections – although the elections 2006 were held in all districts using mixed (proportional representation and majority) systems, in Tbilisi’s proportional elections all mandates of an electoral district would be ceded to the Party with the greater number of votes. This is a system so uniquely unreasonable that it might be found only in countries like Chadi, Cameroon, and Djibouti.

Out of 37 seats, only twelve were allocated to proportional representation party-lists. This system won the opposition only three places (8%) in the City Assembly, when it had actually obtained as much as 31.56% of votes in the capital.

In the proportional representation elections, as compared to the previous elections, the electoral threshold increased as well, reaching 5%. When it comes to majoritarian candidates, they had to obtain the greatest number of votes for victory. Thus, all over Georgia, 1694 assembly members had to be elected: 1 014 – through the majoritarian system, and 680 – through the proportional representation party lists.

Another issue to consider during these elections was that the number of voters suddenly and unexpectedly increased. If, for example, 2 231 986 voters participated in the 2004 extraordinary presidential elections, and 2 343 087 – in the parliamentary elections that same year, the figure increased by almost a million and reached 3 205 634 voters in 2006.

You might remember the period, when Mikhail Saakashvili’s rule gradually began to lose the charm it exuded in the wake of the Rose Revolution as did the trust it inspired both in the society and in many of its political allies: the political alliance, which Saakashvili represented when he came to power, had been dissolved, and street rallies and unrest triggered by the brutal crime that had taken place early that same year – Sandro Girgviliani’s murder – was also gaining ground. Thus, local self-government elections of 5 October took place in such tense political conditions and against the background of the above-mentioned self-government and election “reforms”.

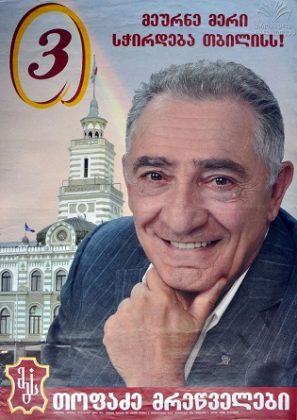

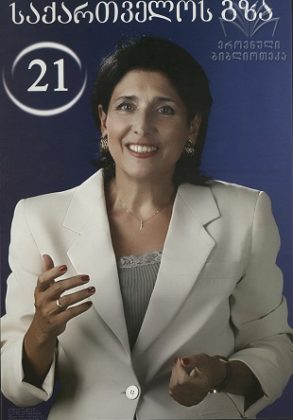

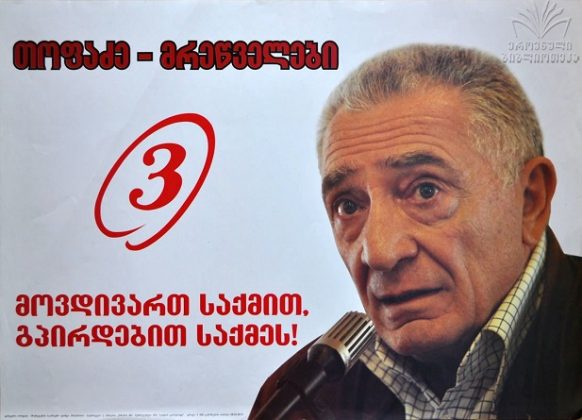

Only six political parties were involved in the race, and even these were not fully represented. Opposition did not even nominate its candidates in a number of electoral districts, and the governing party had no competitors to defeat. “Do not Stay Home, Do not Halt Building [process]“ – this was the UNM’s main motto; its former allies and current opponents – Davitashvili, Khidasheli, Berdzenishvili (Georgia’s Republican Party – Conservators) believed that they could and would change (“We Can – and We Will Change”), while Topadze – Industrialists and their candidate Gogi Topadze claimed that Tbilisi needed an industrialist mayor (“Tbilisi Needs an Industrialist Mayor”)…

The country was once again filled with colourful election posters, the opposition was again complaining that the ruling party was using both financial and administrative resources to its own advantage, and their supporters and members were persecuted and intimidated. The governing party was, of course, denying these charges and it was against the background that the 2006 election was held in Georgia.

The results reflected both centralisation and the weakening power of the opposition: the UNM obtained 85% of votes (equalling 578 mandates) in proportional representation elections, and 92% (925 mandates) in majoritarian elections all over Georgia. The second place went to Davitashvili, Khidasheli, Berdzenishvili (the Republican Party of Georgia – Conservatives), which won 45 proportional and only 9 majoritarian mandates; the Labour Party accumulated 34 mandates in proportional representation elections, and 5 mandates in majoritarian elections. Topadze – Industrialists also overcame the threshold and secured 23 mandates, with only 4 mandates in majoritarian elections. The proportional representation elections threshold was not overcome by Salome Zurabishvili’s Georgia’s Way, however, she managed to win 3 majoritarian places all over Georgia. Further, only 68 people nominated by initiative groups all over the country became majoritarian deputies.

As for the capital’s results, the candidates of the UNM won in all 25 majority districts, while the party received 9 mandates through the proportional representation. In Tbilisi’s Assembly, ‘the winner takes it all’ principle left only 3 nominal places for opposing electoral units: the Alliance of Republicans and Conservatives, the Labour Party, and Topadze – Industrialists took one seat each. Overall, of 37 seats in the capital’s representative body, the ruling party won 34, and the opposition managed to secure only 3 seats.

In total, the UNM secured 925 of 1014 majoritarian mandates, and only 89 mandates were delegated among the remaining opposition parties and independent candidates. Of 680 mandates delegated through the proportional representation, the UNM won 578, and the opposition obtained only 102 mandates.

This was the very purpose of this unreasonable and unjustified self-government reform – concentration of all levels of authority within the small elite’s hands and establish the total control, which remains hitherto unchanged.

30 May 2010 – Tbilisi is allowed to elect its mayor as self-governments are robbed of financial control

The raids on 7 November 2007, subsequent snap presidential elections, 2008 hunger strike, August war, and more occupied villages, large-scale street rallies in 2009, and calls for Saakashvili’s resignation – these are the grave political events with which the country welcomed the 2010 elections.

Amid this political crisis, in July 2009, in parallel to the so-called Cell Protests, the government decided to hold 2010 self-government elections in late May instead of the usual date in October defined by the law. Then appointed Mayor of Tbilisi, Gigi Ugulava, announced the initiative for direct mayoral elections in Tbilisi. Saakashvili went even further by declaring that all mayors would be directly elected in the upcoming elections. Notably, he made this statement during his speech at the UN General Assembly meeting. However, in the end, the President went back on this promise, and mayoral elections were held only in Tbilisi. 30% victory threshold was determined.

Another amendment to the Election Code concerned Tbilisi, which increased the number of the City Assembly members to 50. Of these, 25 would be elected through proportional representation party-lists, and 25 – with majoritarian system in single-mandate districts. In the remaining parts of Georgia, everything remained unchanged as compared to 2006.

What was the condition of self-governance by that time? We can boldly argue that is was way worse than before. The reason was that the municipalities that already had too many financial problems grew poorer. If in 2006 the government took the profits tax from local budgets and sent it entirely to the central budget, later, in 2008, municipal budgets were also deprived of the income tax and subjected to the central budget. After this unjust decision, property tax was the only local tax that the local self-governments maintained. This led to the full financial subjugation of local authorities to the central government by robbing them entirely of the already struggling level of independence.

In parallel to this, apart from expenses to fulfil their duties and responsibilities, municipalities were required by the government to contribute to the central authority’s costs. You might remember that it was about that same period that the MIA (Ministry of Internal Affairs) commenced the opening of new police buildings. These buildings were mostly built at the expense of local budgets. Self-governments also had to cover the expenses made by the bureaus of the parliament’s majoritarian deputies, as well as many other things that was not legally required of them. If this vicious practice was initially informal and based on the oral orders of the government officials, it was officialised in 2009. Per 2008, for example, forced and unjustified expenses of municipalities reached 130 million Gel, and the amount was annually increasing.

It was in these grave political conditions and totally centralised governance system that the governing party and its mayoral candidate GiGi Ugulava launched their election campaign with the following motto: “There’s Much More to be Done” (symbolically perhaps, the Communist party had used the same words back in 1982). As in the previous years, the National Movement did not betray its tradition of preparing campaign videos – “Batums Katkatas” [To Snow-White Batumi] performed by Sofo Nizharadze, in the Party’s view, reflected the reconstruction and prosperity in towns and cities all over the country.

It was in these grave political conditions and totally centralised governance system that the governing party and its mayoral candidate GiGi Ugulava launched their election campaign with the following motto: “There’s Much More to be Done” (symbolically perhaps, the Communist party had used the same words back in 1982). As in the previous years, the National Movement did not betray its tradition of preparing campaign videos – “Batums Katkatas” [To Snow-White Batumi] performed by Sofo Nizharadze, in the Party’s view, reflected the reconstruction and prosperity in towns and cities all over the country.

The opposition’s major mottos were also rather irrelevant in terms of self-government functions and powers. For example, the alliance of the Christian-Democratic Union (which included the Christian-democratic movement, Chven TviTon [Ourselves], and the Christian-Democratic People’s Party) and their candidate Giorgi Chanturia promised the population lowered fees of gas, electricity, and water (“Gas – 10 Tetri, Electricity – 5 Tetri, Water – free”), when such such fees had never been included within the competence of self-governments.

Irakli Alasania, who had just moved to the opposition’s side, represented a new alliance formed by Liberal Democrats, Republican Party, New Rights, and Georgia’s Road. His motto ran as follows: “We Will Change.”

The chief message of the National Council and its candidate Zviad Dzidziguri had even greater problems of compliance – “Fight Today!” Apart from the fact that this motto had nothing to do with what self-government generally is, Dzidziguri and the National Council (which included many parties), who organized the street protests from 2007 to 2009, had been fighting to change Saakashvili’s regime for years already, and it was uncertain how they were actually going to begin their fight “today or right away”.

Industry Will Save Georgia’s major mayoral candidate – Gogi Topadze – promised the electors to do business (“I Am Coming with Business, I Promise Business”).

Overall, 17 electoral alliances and political parties participated in the 2010 self-government elections, and 9 candidates were competing for the mayor’s office. The electoral period was, of course, very tense. Opposition was daily reporting cases of persecution and intimidation their members or followers were subject to, and complaining about the ruling party’s abuse of administrative resources to its benefit.

Although the UNM kept denying these charges, figures from that period speak for themselves and demonstrate the increase of public finances as well as the number of self-government’s employees. For example, in 2010, as compared to the previous year, the volume of the transferred funds grew by 34%. That same year, unjustified expenditure of Tbilisi budget hit 84 million. The number of self-government employees was also rising. We know the number of employees in municipal bodies soared from 6 to 12 thousand people between 2006-2012, while 50 000 people had been employed in various LEPL-s (Legal Entity under the Public Law) founded by local self-governments outside Tbilisi.

The local self-government election was monitored by 26 local and 28 international observation missions, including OSCE. In many polling places, local observation organisations identified numerous breaches. For example, observers of Fair Elections were not allowed to enter the polling places and stations, and they were subject to oppression; there were multiple cases when marking devices were not used, certain individuals voted using other people’s ID cards, or the same person voted several times; number of voters had been substantially increased in the additional lists, and the number of voting papers in many vote boxes exceeded the number of signatures on voters lists.

Election results proved to be reflective of the pre-election environment – the ruling UNM won 65.75% of votes all over Georgia in proportional representation elections. The second place – 11.94% of votes – went to Giorgi Targamadze and Inga Grigolia – Christian-Democratic Union; the third place with 9.19% of votes went to Irakli Alasania’s alliance – Alliance for Georgia; the National Council gained the fourth place with 6.77%. Other electoral units could not overcome the threshold.

If we deduct Tbilisi’s results from the data, it is evident that the governing party accumulated more than 73.9% in the remaining parts of Georgia.

When it comes to Tbilisi, here the UNM collected 52.5% in proportional representation elections. The second place – 17.97% – went to the Alliance for Georgia; Christian-Democrats gained the third place with 12.05%, and the national council took the fourth place here as well with 8.26%. Topadze-Industrialists also entered the capital’s council with 6.23% of votes.

Unlike the proportional representation elections, the opposition could not win any majoritarian mandates in the capital, and all 25 seats in the Assembly were taken up by the governing party. It was exactly through this mixed electoral system that the UNM secured 78% of mandates in the City’s Assembly. The capital’s mayor became Gigi Ugulava in the very first round, with 55.23%. His main competitor Irakli Alasania gained only 19.05%. Although the opposition was protesting the election results, Alasania soon admitted his defeat and officially congratulated Ugulava on his victory.

When it comes to the remaining regions, the UNM managed to gain 958 mandates in majority elections, Topadze-Industrialists – 26, Christian Democratic Movement – 12, Alliance for Georgia – 5, United National Council – 4, and 13 mandates were obtained by representatives of various parties.

15 June 2014 – nation-wide reform of self-government, increased number of self-governing cities, and direct election of mayors and Gamgebelis

Georgia met the 2014 local self-government elections with an entirely revised legislation and positive expectations in this regard. The reform that began soon after the Georgian Dream Coalition came to power aimed to implement genuinely transformational changes: maximum differentiation and clarity of the competencies and functions of the central authorities and local self-governments as well as the extension of the latter’s authority, administrative and territorial reform, increasing the number of self-governing towns, re-establishment of the two-level self-government, election for mayors and Gamgebelis, fiscal and property decentralisation – this is a short list of those promises that the governing party undertook to implement. As part of these obligations, Georgian Government first approved “the Strategy for the Decentralisation of the Georgian Government and the Development of Self-Governments” in 2013, and then, in 2014 the Georgian parliament approved the “Local Self-government Code”.

In a word, hopes were harboured that finally, 23 years since the restoration of the national independence, we would receive an independent, strong system of self-government with adequate competencies, finances, and assets, which could and would no longer be used by the central government and the ruling party for their political gain.

Thus, we had regained the right to direct election of mayors and Gamgebelis in 2014. Besides, 5 self-governing cities – Tbilisi, Rustavi, Kutaisi, Batumi, and Poti, as well as 7 more towns of Zugdidi, Ozurgeti, Gori, Akhaltsikhe, Telavi, Mtskheta and Ambrolauri were added. In parallel to the establishment of these self-governing cities, community municipalities of the same name were formed, which united all relevant villages and urban settlements. These self-governing towns and community municipalities were given equal opportunities for development.

Considering this change, Georgian population had to elect mayors of 12 cities and Gamgebelis of 59 community municipalities. If the threshold during the 2006 mayoral elections (Tbilisi) was 30%, now, all over the country, the candidate that overcame 50% would be named winner in both mayoral and Gamgebeli’s elections. As for the elections of assembly members, electoral threshold for proportional representation system amounted to 4%, and in majoritarian elections, the candidate with greater number of votes would be named winner. Overall, at 2014 elections, we had to elect 2088 deputies of Sakrebulo [City Assembly] – 1 050 through proportional representation, and 1 038 – through majoritarian system.

It is natural, however, that the change and refinement of legislation did not itself alter the political climate. Many areas of conflict emerged 2012-2014 as the Georgian Dream formed the central government, and the UNM was in charge of the local authorities. In some cases, the Dream’s local organisations used rallies and picketing to force Gamgebelis into resigning. Some active members of assemblies moved to the parties inside the Dream coalition, completely overturning the balance in many representative bodies.

In these conditions, 24 electoral units from all over Georgia, and 19 electoral units in Tbilisi decided to participate in the elections. 14 candidates had been fighting for the status of the city’s mayor, with two being the most prominent competitors – the Dream’s Davit Narmania and the UNM’s Nikanor Melia. Overall, in 12 self-governing cities, 87 candidates had been fighting for mayorship, while only 262 candidates desired to obtain the Gamgebeli’s post in other municipalities.

The electoral campaigns of the candidates did not stand out with their ingenuity and largely resembled those from the previous years – jammed with posters, leaflets, and billboards, and the heightened activity in social networks was the only novelty. “Let’s Take Care of Tbilisi Together” – this was Narmania’s pre-election motto (mottos of other candidates sounded similar as well – “Let us Look After Batumi / Terjola / Georgia together”).

Melia, on the other hand, promised voters to make the capital work (“We Will Make the Capital Work Together”).

Asmat Tkabladze, the Labour party candidate, stood out with a very ingenuine motto – “You Know What to Do, Tbilisians!”

The first round of the elections identified only 50 mayors all over the country, and all winners were the GD’s candidates. The second round was appointed in 8 self-governing cities and 13 community municipalities. The same was true of the capital as well, which required the second round to identify the mayor; here you might remember the winning party’s premature firework celebration of Narmania’s victory in the first round upon the closure of polling stations. Overall, as a result of the second round held in 21 municipalities, the GD’s candidates secured their victory; it is still noteworthy, however, that in the wake of the new self-government reform, holding the second round was itself a small, but positive step taken toward the country’s democratisation.

As for the Sakrebulo’s elections, of 2088 deputies elected from all regions of Georgia, 718 (34.3%) were independent or opposition’s candidates. These included representatives of those parties that could not overcome the 4% threshold established for the proportional representation but managed to win in the majoritarian elections. The same was true of the municipalities, in which representatives of opposition parties and independent deputies outnumbered the members of the ruling party in the assembly. For example, in Chkhorotskhu’s representative body, the opposition / independent deputies gained a total of 16 seats, while the GD had – 12; the opposition and independent deputies had 17 seats, and the GD – 14 in Abasha; while in the self-governing city of Ozurgeti 10 seats went to the opposition and independent candidates, while the GD gained only 5…

When it comes to Sakrebulo’s proportional elections, if the governing party managed to obtain 50.82% of votes nationwide, it won no more than 46.01% in Tbilisi. The National Movement, on the other hand, gained 22.42% all over the country, and secured 26.11% in Tbilisi. The following parties managed to overcome the 4% threshold: Nino Brjanadze – United Opposition – 10.22%, Davit Tarkhan-Mouravi – Patriots Alliance – 4.72%. These two parties also entered the City Assembly: Patriots Alliance obtained 6.35%, and Burdjanadze’s party – 10.35%.

21 October 2017 – elections are held as 7 cities are robbed of their self-governing status, and the reform is suspended

The great expectations and high hopes related to the 2014 self-government reform were gravely shattered not long before the 2017 elections. The Local Self-Government Code demanded of the government to make income tax shared as early as in 2014, and leave its portion in municipal budgets; it had to develop a fair and non-discriminatory rule for the allocation of equalization transfer; establish criteria for the territorial optimization of municipalities, elaborate the procedures and timeline for the allocation of agricultural lands among municipalities by 2017, etc. These actions would ensure the establishment of independent and strong, empowered self-governments in terms of both finances and assets.

Instead of the above-mentioned course, however, the governing elite, which had substantially changed its initial composition from 2014, took radically different decisions, and refused to proceed with the implementation of those minor improvements that it had made between 2014 and 2017.

You might remember that not long before the self-government elections, upon Kobakhidze’s and Kvirikashvili’s personal initiative, against the will of the protesting local population and civic society, and in grave and evident breach of the Law, the seven cities that had been established as municipalities back in 2014 were now robbed of their self-governing status and included in the community municipalities. The President of Georgia even vetoed this decision of the Parliament; however, the GD’s parliamentary majority managed to override the veto and left the country without these self-governing cities before the 2017 elections.

Kobakhidze then claimed that such a decision would improve cost efficiency, which was an outright lie (my reader will necessarily remember how the UNM used the same motive to justify the abolition of the first-level self-governments. It is notable here that this same reform was approved and positively assessed by ‘expert’ Kobakhidze, who viewed it as a step taken toward decentralization).

In truth, though, the reason behind the abolition of the self-governing cities was quite simple and hackneyed: the ruling party, now with severely diminishing popularity, would have to compete in seven fewer municipalities. This may be evocative of the fact that the ruling party’s candidates had to fight for the victory in the second round in 4 of the newly formed self-governing cities in 2014 – Ozurgeti, Gori, Mtskheta, and Telavi as well as in the newly created community municipalities of Gori and Telavi.

Interestingly, the GD was also discussing the abolition of direct mayoral and Gamgebeli elections during the intra-party debates in those days, however, the massive protests sparked by the abolition of the self-governing cities dissuaded the government from taking this risk.

Moreover, the government also abandoned the course of fiscal and property decentralisation and left impoverished and destitute municipalities dependent on the central budget, placing them in a ‘beggar’s’ position once again.

In parallel to this, the political situation in the country was growing tense and grave. The GD was the only party that remained in power from the entire political coalition of 2012. Other members of the alliance moved to the opposition from 2016. From elections to elections conducted under the GD’s rule, the governing party was increasingly abusing the administrative resources, oppressing, persecuting, and intimidating the opposition’s members and followers.

This was the general background for the 2017 self-government elections held in 59 community municipalities and five self-governing cities. The election procedures had not been amended since 2014 – mayors / Gamgebelis would be elected with 50%+1 of votes; as for the mixed system of Sakrebulo’s elections, parties had to overcome the 4% threshold for proportional representation, and the majoritarian candidates needed to gain the biggest number of votes. The only change was the titles – executive officials elected on 21 October would be referred to as ‘mayors’ in both communities and self-governing cities, and self-government bodies would be elected for a 4-year term as the transitional three-year period ended in 2017.

Twenty-six (26) political units from all over the country, and 16 from Tbilisi obtained the right to compete in the elections. Thirteen (13) candidates had been racing for the office of the capital’s mayor. Kakha Kaladze, the ruling party’s candidate, promised us “Tbilisi – a City of Life”, and we still watched the GD’s branding video – “Chemi Sakartvelo Ak Aris” [My Goegria Is Here] on TV. The UNM’s candidate Zaal Udumashvili wished to turn Tbilisi into a city of employed, successful and happy people; Elene Khoshtaria – the European Georgia’s candidate – promised to take steps towards the European integration (“A Step Towards Europe”), Davit Usupashvili’s Movement for Building offered to build in the right manner (“It’s Time to Build Correctly”); the Labour Party still remained loyal to its motto of vital fight, while Burdjanadze’s Democratic Movement promised to return Tbilisi [to its population] (Let’s Return Tbilisi); Giorgi Vahadze called for the change of the government for greater success (“Change for Success”), while the Republican Party promised to bring peace, and deliver us from all troubles. Independent mayoral candidate Aleko Elisashvili had the simplest and the most candid motto – “Aleko as Mayor”.

We, voters, had to choose among these election promises, and here is the choice we made. In the capital, Kakha Kaladze survived the second round by 1.09%, and 51.09% of votes made him the city’s mayor in the first round. It is noteworthy that Aleko Elisashvili proved more successful than other candidates and secured the second place with 17.48% of votes. The UNM’s candidate Zaal Udumashvili managed to accumulate 16.59% of votes, while Elene Khoshtaria, the European Georgia’s candidate, gained 7.11%. Others failed to obtain more than 3% of votes.

The City’s Assembly (Sakrebulo), as usually characteristic of one-party, centralised rule, nominally included opposition members: only three opposition parties managed to overcome the threshold in the proportional representation system – the European Georgia, the UNM, and the Patriots Alliance won a total of 10 mandates. The ruling party secured 15 mandates, fully won all 25 majoritarian districts, and obtained a total of 40 assembly seats.

Results of the remaining election districts were not very different from those of Tbilisi. If during the 2014 elections the second round was conducted in 21 municipalities, 3 years later it was needed in only six municipalities, of which only one was a self-governing city (Kutaisi), while the remaining five (Kazbegi, Khashuri, Borjomi, Ozurgeti, and Martvili) were community municipalities. This once again evidences the real reason and purpose behind the abolition of the above-mentioned 7 self-governing cities.

Of mayors elected in the very first round, only Tamaz Mechiauri did not represent the Georgian Dream. You might remember that he defeated the opponent by 1 vote. As for the results of the second round, the GD’s candidates won the elections in five of the six above-mentioned municipalities. The UNM and its candidate boycotted the second round in Kutaisi and Martvili, while in Ozurgeti, where Konstantine Sharashenidze competed as an independent candidate, the results of a single polling place (Nasakirali polling station) proved decisive, and the ruling party’s candidate was defeated. It is, however, notable that both Mechiauri and Sharashenidze were former members of the GD, and despite opposing the party itself, they remained faithful to the party’s founder and leader Bidzina Ivanishvili.

As for the Sakrebulo elections, of 2058 deputies elected nationwide, only 21.7% (448) were the opposition members or independent deputies. In the 2014 elections, this figure equalled 34.3%, and in the wake of the large-scale self-government reform, many had cherished false expectations for increasingly pluralist representative bodies at the local level.

In reality, this was the reason why the GD began to walk the UNM’s path, halted the decentralisation process, and took a step backward to the authoritarian rule.

2 October 2021 – a referendum or another chance to solidify the authoritarian rule?

We will be arriving at polling places in no more than three weeks and elect our representatives – mayors and Skarebulo’s members – in local self-government elections. Based on the results of the parliamentary elections held last year, protests of the opposition and the civil sector, and Charles Michel’s compromise document, the opposition views these elections as a referendum. Meanwhile, the ruling party, which annulled the document, travels from region to region and promises local population to expect prosperity from the centre.

Shall we see the repetition of the 2002 elections, and will the opposition manage to change the government using the same scenario? We shall see. As of now, it is the most unfortunate and saddening fact that as many as 30 years after the restoration of independence, the country’s political elite does not even mention the empowerment of local self-governments and decentralisation, not to speak of their political agenda. Such attitude to local self-government led the UNM, and now the GD to the authoritarian rule. Unfortunately, the country’s politicians and policy makers seem unable to learn from the valuable lessons that the history of self-governments offers.

The article draws upon the following:

Materials and data of the Central Elections Commission

Research: “Local Democracy Development Report” (iccc; osgf)

Photo materials preserved in the archive of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia

Read in Georgian at the link